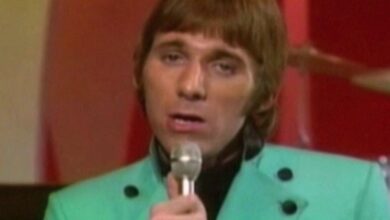

Everything Is Beautiful: Ray Stevens and the Three-Minute Pop Sermon That Still Works

Everything Is Beautiful: Ray Stevens and the Three-Minute Pop Sermon That Still Works

In the spring and summer of 1970, American radio was crowded with big feelings and bigger personalities, yet Ray Stevens slipped something unusual into the middle of the noise: a gentle, singable message that sounded like it belonged to everyone. “Everything Is Beautiful” wasn’t built like a novelty record, even though Stevens was already famous for humor and character songs. It arrived with warmth instead of punchlines, carrying a simple idea—people are different, and that’s not a problem to solve, it’s a truth to celebrate. The result felt less like a performance and more like a public handshake: friendly, a little earnest, and surprisingly brave for the moment it landed.

What made the song hit so hard was how plainspoken it was without being preachy. Stevens wrote it as a theme for his 1970 television work, and it carried that “broadcast to the whole country” clarity—short lines, clear images, and a chorus that anyone could remember after one listen. The lyric isn’t complicated, but the intention is: it asks listeners to stop sorting each other into categories long enough to notice the human being in front of them. Even today, the lines about hair, skin, and judging feel direct in a way that many “message songs” avoid. It’s not trying to win an argument; it’s trying to disarm one.

Musically, it’s deceptively smart. The arrangement sits in a soft, pop-country pocket with a bright, welcoming rhythm that never rushes. The melody is built to be hummed by people who don’t consider themselves singers, and that matters, because “Everything Is Beautiful” works best when it feels communal. There’s also a storytelling trick inside it: the track uses child voices to widen the emotional frame. Kids don’t make the message deeper in a philosophical sense, but they make it feel more urgent and sincere, like a reminder from the part of the world that hasn’t learned cynicism yet.

That children’s chorus wasn’t just a studio gimmick, either. The original recording famously included local schoolchildren, and the presence of young voices gave the song its signature glow. It changes the energy of the chorus from “an adult making a point” to “a room full of people agreeing.” It also made the record stand out on radio at a time when production was becoming increasingly polished and adult-coded. Stevens, intentionally or not, created a sound that felt like a neighborhood rather than a spotlight. The message lands because it sounds like it’s being shared, not sold.

Commercially, it wasn’t a minor success; it was a real, chart-dominating moment. “Everything Is Beautiful” reached the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in 1970 and stayed there long enough to become part of the season’s soundtrack, not just a one-week novelty. It also crossed over strongly to adult audiences, fitting right into the easy-listening and adult contemporary world where sentiment, clarity, and melody mattered. That crossover is a huge part of why the song became a “pop standard” rather than a time capsule. It didn’t belong to one youth scene or one region; it belonged to living rooms, car radios, and family gatherings.

Awards culture noticed, too, and that’s one of the clearest indicators that the industry understood this as something more than a catchy single. Stevens won a Grammy for his vocal performance of the song, and the tune also became associated with inspirational music recognition in the same era through other renditions. The key point isn’t the trophy count; it’s the shift in perception. “Everything Is Beautiful” reframed Ray Stevens in the public eye as an artist who could do more than make people laugh. It showed he could deliver a sincere statement without losing his identity, which is harder than it sounds when an audience thinks it already knows what you are.

The record also captured a particular American tension: the desire for unity at a time when unity felt impossible. In 1970, the country was exhausted by conflict, generational suspicion, and cultural fragmentation, and “Everything Is Beautiful” offered a soft counterspell. It didn’t deny the chaos; it simply refused to let chaos be the only story. That’s why the song keeps resurfacing. Every few years, someone hears it again and realizes it’s not just a vintage feel-good track. It’s a small piece of musical optimism that dares to say we can do better—without yelling, without scolding, and without pretending the problems aren’t real.

One reason live performances of the song still land is that they reveal how much of its power is carried by Stevens’ timing and tone. In the studio, the track feels polished and carefully balanced, but onstage it becomes more conversational, like a seasoned entertainer stepping forward to say something he still believes. The best live versions don’t overplay the sentiment; they let it float. That restraint is what makes the moment feel different from many “inspirational” performances. Instead of chasing tears, it invites a smile first—and then, almost accidentally, you realize you’re feeling more than you expected.

That live moment matters because it highlights something the studio track can only hint at: how naturally the song sits in a room. The message becomes less like a statement and more like an atmosphere. You can hear how the chorus is designed to be joined, not merely heard, and you can feel why audiences respond even when they know every word. It’s also a reminder that the song’s optimism isn’t fragile; it’s performable. When a piece survives outside its original production and still feels credible, it earns a different kind of respect. The performance turns the song into proof that simplicity can be sturdy, not shallow.

The studio recording, by contrast, is where the craftsmanship shows up in full. The runtime is about three and a half minutes, and in that tight window Stevens manages to set a scene, establish a moral, and leave room for the chorus to feel inevitable rather than forced. The production is clean without being cold, with an arrangement that supports the lyric instead of competing with it. The child voices don’t feel pasted on; they feel integrated into the track’s emotional logic. This is also where Stevens’ vocal approach shines: friendly, slightly smiling, never pushing too hard. He sounds like a narrator you trust, which is exactly what a message song needs if it’s going to avoid sounding like a lecture.

Hearing another classic vocalist interpret the song in a live setting underlines how flexible the composition really is. “Everything Is Beautiful” can be delivered as pop, lounge, country-pop, or easy listening without breaking, because the melody is sturdy and the lyric is clean. In a more theatrical performance style, the song can lean into polish and control—longer phrases, smoother dynamics, a slightly grander emotional arc. That contrast helps explain why Stevens’ own versions feel different: his delivery often carries a homespun humility, like he’s deliberately stepping back so the message can step forward. The song survives both approaches, but the emotional temperature changes dramatically depending on who’s holding the microphone.

A modern concert interpretation from a different corner of pop and adult contemporary can make the track feel like a communal hymn rather than a nostalgic single. In these performances, the audience reaction becomes part of the arrangement—applause patterns, quiet listening, the way a room leans in on familiar lines. The lyric’s emphasis on acceptance tends to hit differently in later decades, too, because the cultural debates it touches never fully disappear. What’s striking is how the song can feel both gentle and pointed at the same time. It doesn’t name political camps or social tribes, but it still asks a clear question: why are we so committed to dividing up something as basic as human worth?

Later-career versions—especially anniversary-style recordings and performances—add another layer: time. When Stevens revisits “Everything Is Beautiful” decades after it first topped the charts, the song stops being just a snapshot of 1970 and becomes a personal statement across generations. The same chorus can carry new weight when delivered by an older voice that’s seen the country cycle through unity and division again and again. This is where the “what makes this version different” question becomes real: the best later performances don’t try to recreate youth. They lean into perspective. The message becomes less like idealism and more like insistence—an artist returning to an idea because he still thinks it matters, and because he’s watched how often it gets forgotten.