Peter, Paul And Mary’s “Early Morning Rain” Is The Sound Of A Goodbye You Can’t Board

Peter, Paul and Mary had a gift for turning other people’s songs into lived-in stories, and “Early Morning Rain” is one of their most quietly devastating examples. In the mid-1960s folk boom, plenty of groups could harmonize sweetly, but not everyone could make three voices feel like one shared thought. Their recording lands like a photograph you didn’t know you still carried: an airport fence, a pocket with a little cash and a lot of emptiness, and the strange humiliation of watching a plane do what you can’t. The trio doesn’t oversell it. They let the lyric do the heavy lifting, and that restraint is exactly why it hits so hard, decades later, in any era where distance and longing still feel like daily weather.

The song itself begins with an image so plain it almost feels accidental: early morning rain, a dollar in hand, pockets full of sand. But the genius is how quickly that simple setting becomes a complete emotional map. “Early Morning Rain” is about being stranded in every sense—geographically, financially, and spiritually—while the world keeps moving with mechanical certainty. Written in the jet age but emotionally ancient, it’s a modern hobo ballad with a runway replacing the railroad yard. Peter, Paul and Mary understood that immediately. They don’t treat it like a clever concept song. They treat it like a human confession, one that doesn’t ask for pity, only understanding.

By the time the trio recorded it in the mid-1960s, the folk scene was filled with songs that pointed outward—protest, politics, public change—and songs that turned inward—private ache, personal reckonings, the soft grief of everyday life. “Early Morning Rain” sits in that second category, but it carries the scale of the first. It’s not a love song in the traditional sense, yet it’s drenched in longing. It’s not a protest anthem, yet it quietly critiques the way progress can leave people behind. Peter, Paul and Mary deliver it with the calm of storytellers who know the audience will recognize themselves somewhere between the fence and the sky.

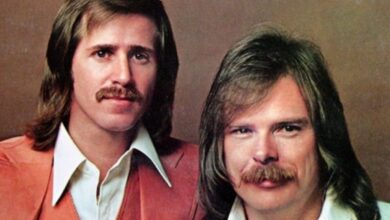

What makes their version different is the way the arrangement frames the narrator as both solitary and surrounded. Peter Yarrow’s warmth steadies the center, Noel Paul Stookey’s phrasing gives the lines a conversational ache, and Mary Travers brings that unmistakable clarity—big enough to fill a hall, gentle enough to sound like she’s singing to one person. The harmonies aren’t decorative. They function like memory, like thoughts echoing back at you when you’re alone. Instead of letting the song become a showcase for vocal fireworks, they keep it grounded, almost journalistic in its simplicity. That choice makes the emotional punch feel earned rather than manufactured.

There’s also a very specific Peter, Paul and Mary quality to the pacing. They knew when to lean into a phrase and when to let silence do the work. The song’s power depends on the feeling of time passing slowly—standing there, watching departures, realizing you are not one of them. Their tempo never rushes that heartbreak. The guitar work stays supportive, like steady footsteps on wet pavement. The trio’s phrasing turns “early morning rain” into a mood rather than a forecast. It becomes the sound of a day that’s started without you, the kind of morning where you’re awake too early not because you’re inspired, but because you’re stuck with your thoughts.

A lot of covers treat “Early Morning Rain” as a straightforward folk standard: pretty chords, pretty melody, done. Peter, Paul and Mary treat it like a scene. You can feel the fence line, the runway lights, the aircraft thunder, the sting of being close enough to watch but too far to touch. Their best recordings often create a sense of place—“Puff” has a coastline, “Leaving on a Jet Plane” has a doorframe goodbye—and “Early Morning Rain” has an airport that feels cold even when the room you’re listening in is warm. That’s why it’s never just background music. It demands attention without demanding applause, which is an underrated kind of mastery.

The irony is that the song’s central drama is intensely physical—planes lifting, engines roaring, the body wanting to move—but the emotional experience is static. You’re frozen while everything else accelerates. Peter, Paul and Mary capture that paradox by singing with a kind of controlled stillness. Their voices do not chase the plane. They watch it. That observer’s posture is what makes the final lines land like a quiet verdict rather than a dramatic twist. The narrator doesn’t explode; he accepts, bitterly, that some things can’t be jumped or stolen or improvised your way into. Sometimes the distance wins, and all you can do is name it.

And yet, for all its melancholy, their version isn’t hopeless. There’s tenderness in the way they hold the melody, as if the act of singing the story is itself a small rescue. Folk music at its best has always been about giving shape to feelings that otherwise sit wordless in the chest. Peter, Paul and Mary do that here with almost surgical precision. Their “Early Morning Rain” doesn’t try to rewrite the narrator’s fate. It simply makes the loneliness legible—and that, in its own way, is a kind of companionship. It’s why the song still travels, even when the singer cannot.

In live performance, the song’s quiet strengths become even clearer because the room itself adds a new layer: shared silence. A good audience doesn’t treat this one like a singalong stunt; they listen the way people listen to a story that might be about them. The trio’s live approach keeps the intimacy intact even as the setting grows. That’s the hallmark of Peter, Paul and Mary at their peak—stadium-sized reach with living-room closeness. In a live “Early Morning Rain,” you can feel how carefully they manage dynamics: the soft lift of harmony on key phrases, the way Mary’s voice can brighten a single line without turning it theatrical, the way the final moments arrive like a door closing gently instead of slamming.

The studio version’s particular magic is how “unproduced” it feels, even though it’s clearly arranged with intention. There’s no sense of gimmickry, no sonic tricks trying to make the sadness bigger than it already is. Peter, Paul and Mary were experts at sounding like themselves—human, direct, emotionally present—rather than sounding like a trend. That matters with this song, because “Early Morning Rain” is vulnerable by design. Any extra sheen risks turning it into something sentimental or slick. Their recording stays textured and honest, like paper worn thin from being folded too many times. You hear the space between the voices, the small breaths, the steadiness. It feels less like a performance and more like a memory you can replay.

Hearing the songwriter’s own studio recording beside Peter, Paul and Mary’s version is like comparing two photographs of the same place taken on different days. Gordon Lightfoot’s delivery carries the author’s authority—the sense that the image came from a real emotional geography and not just clever writing. His phrasing often emphasizes the narrator’s isolation as something almost stubborn, a man talking himself through the humiliation of wanting what he can’t reach. Peter, Paul and Mary, by contrast, soften the edges without dulling them. Their harmonies make the loneliness feel communal, as if the narrator’s private ache belongs to a larger human experience. Both readings are powerful, but they tell the story from different angles: one from inside the narrator’s head, the other from a sympathetic distance.

A later live performance from Lightfoot shows how the song matures with time, and that comparison helps explain why “Early Morning Rain” refuses to age out. In a mature live setting, the lyric can feel less like youthful frustration and more like seasoned regret—the kind that doesn’t flare up, but sits quietly and permanently. The melody holds up because it’s built on strong bones, and the story holds up because the feeling is universal: watching something leave without you. Set against Peter, Paul and Mary’s gentler blend, Lightfoot’s live presence can feel more solitary and narrative-driven, like a man recounting a scene he still sees when he closes his eyes. It’s the same song, but the emotional temperature shifts, proving the writing is deep enough to handle multiple lifetimes.

Ian & Sylvia’s connection to the song adds another dimension, especially when the performance includes Lightfoot himself. That combination turns the piece into folk history happening in real time—artists trading a story that has traveled through different voices and still remains intact. In this kind of performance, you can hear how the song functions like a standard without becoming generic. Each singer highlights a different bruise. Ian & Sylvia often bring a conversational earthiness, a sense that the narrator isn’t a poetic archetype but a real person in real weather. Place that beside Peter, Paul and Mary’s polished intimacy and Lightfoot’s authorial calm, and you get a fuller portrait of why “Early Morning Rain” became a song so many great artists felt compelled to carry.

What ultimately makes Peter, Paul and Mary’s version special is how it balances beauty and pain without letting either one cheapen the other. The harmonies are gorgeous, but they never distract from the story. The sadness is heavy, but it’s never melodramatic. Their arrangement respects the lyric’s humility: a person with almost nothing, wanting one simple thing—home—and realizing he can’t buy it, steal it, or leap into it. That’s why the song keeps finding new listeners. You don’t need to know the 1960s folk scene, the jet-age symbolism, or the backstory. All you need is one morning where you felt left behind by life’s momentum. Peter, Paul and Mary meet you right there at the fence.

And in a broader sense, “Early Morning Rain” is a perfect example of why Peter, Paul and Mary mattered beyond the hits people automatically name. They were interpreters with empathy. They could take a songwriter’s private image and turn it into a shared emotional event. That’s not a small skill. In a culture that often rewards volume and spectacle, their “Early Morning Rain” proves the opposite point: sometimes the most powerful performance is the one that refuses to shout. It simply tells the truth clearly enough that the room goes quiet. Long after the last harmony fades, the picture remains—gray sky, wet air, a plane lifting away—and the ache of wanting to follow it.